Integrating User Stories in Project Planning & Deliverable Development

An important part of managing any project is being able to break the project down into its component parts. A good project manager and project team need to know and fully understand what a project is intended to do in order to plan and develop the details of the project deliverables.

Project deliverables, according to the PMBOK Guide, are, “Any unique and verifiable product, result, or capability to perform a service that is required to be produced to complete a process, phase, or project.” (Project Management Institute, 2021). Simply put, deliverables are what a project creates or produces – the output of a project. Those deliverables can be tangible, such as physical objects like products, or intangible, such as events or processes. They define what a project should make or do. When deliverables are correctly defined, each deliverable should come in two pieces. One piece is the deliverable itself and another piece is the associated success criteria for that deliverable. Success criteria can be broadly explained as the criteria used to measure project success (Castro et al., 2019). Success criteria come in a broad range of formats, with elements and standards able to be applied to different projects as appropriate. If a project deliverable is successfully completed, success criteria spell out in detail what that success should look like.

There are a number of different practices for addressing this part of project planning. From informal discussion and consideration to structured, formal brainstorming sessions. User Stories are one tool that every project manager should have in their toolbox for creating and defining project deliverables.

User Stories

A user story is a short statement in the everyday language or business language of the end user of a project’s output that captures, summarizes, and articulates what a user does or needs to do with that output. It states what the user of the project output wants that project output to be able to do or what they want to be able to do with it. User stories describe the features of a projects output from the point of view of an end user.

User stories have their background in agile practices in software development. In this context, user stories are written to describe the features to be included in a software or technology project. Assembled together, the list of user stories makes up the product backlog, or list of features to be built into and included in the project. Based on order of priority, those features are pulled from the product backlog for inclusion in a sprint cycle.

As agile practices have since expanded well beyond the software and general technology sector and into use in all types of projects, so have user stories. They have since become a useful feature in describing the output and elements of various types of projects.

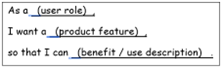

User stories are written in a standardized format. They clearly define the end user in mind (the who), the feature to be described and included (the what), and how the user will use that feature of the product (the why). The format for user stories is, “As a (user role) , I want a (product feature) , so that I can (benefit / use description) . “

Who

The “Who” element describes the role of the user. It asks and answers the question, “who will use the output and receive value from a particular output feature?”.

What

The “What” element describes the product feature itself. This is the deliverable item of the aforementioned output. In agile teams, this would describe one unit of delivery. It is a single, individual feature of a projects output.

Why

The “Why” clearly describes how the user defined in the “who” part of the story intends to use the feature. What will they do with the feature and how does it bring value to the output of the project?

Examples of user stories include:

- As a listener, I need a tuning button, so I can find my favorite radio station.

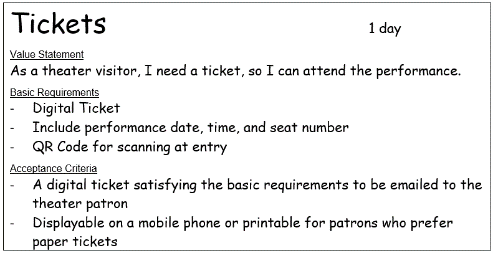

- As a theater visitor, I need a ticket, so I can attend the performance.

- As a convention delegate, I need a schedule of events, so I can plan my day at the convention.

Several slight variations on the format exist, but the general point is always the same – identifying the user, describing the output feature, and detailing its use or function. The elements can be broken down and considered in those three parts.

Advertisement

[widget id=”custom_html-68″]

Story Cards – simplified approach

Story cards are the tools used to create, arrange, and organize user stories. Each story card is a user story as a self-contained description of a project feature, with additional accompanying elements included along with it to help further define the details of that feature. User stories are traditionally written on physical, individual cards in order to establish the details of each user story and to facilitate the reprioritization and rearrangement of the stories for inclusion in the project. In contemporary practice, story cards can be created and arranged in digital form, using various project management, storyboarding, or digital whiteboard software and applications. Any format works, as long as it can be viewed, shared, discussed, and changed by the project team members.

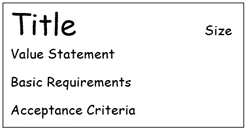

Just as user stories themselves have some slight variations in structure depending on the specific methodology followed, so do story cards. At a basic level, a user story card should include a title, a value statement, basic requirements, size estimation, and acceptance criteria.

Title

The title of the story card is exactly what it sounds like. It is a shortened or abbreviated name of the story. It should be sufficiently expressive to describe the feature it defines. Titles help to organize the stories for arrangement and prioritization.

Value Statement

The value statement is the heart of the story card, presenting the user story itself in the format previously set out. It describes the user role, the feature to be included, and the benefit or use of that feature to the end user.

Basic Requirements

The basic requirements section is a flexible element of the story card and can be used to further define some of the essentials or expectations of the feature or its development. This can include anything from aspects of functionality to resources or constraints in producing the feature. The Basic Requirements element can be included or omitted at the discretion of the project manager or as the feature itself necessitates.

Size Estimation

In agile methodologies, the size estimation is typically done using an estimation point system. In other practical usage, a time estimation is useful to include and sufficient to further define the story. This is done by estimating, in time or work units, how long the feature will take to complete as described.

Acceptance Criteria

Acceptance criteria describe the basic benchmark that has to be met in order to consider the story complete. It is a description of a successfully completed and functional feature. Acceptance criteria can be written by asking and answering the question, “If this feature is successfully included, what does that success look like?”

Application

In agile methodologies such as Scrum, the collection of story cards makes up the Product Backlog, or list of features to be selected for inclusion and built into the project during an iterative sprint cycle. For more traditional methodologies, user stories and story cards can serve a number of roles. They can help to describe and define features of a projects output from an important point of view – that of the end user. In project brainstorming sessions, this approach helps project team members to take on that role in considering features. Once those features are defined, they can be added to the deliverables list for the project, either as final deliverables or for inclusion in an iterative development cycle. Finally, they can be used to supplement a traditional Work Breakdown Structure. In this way, the story cards can create additional WBS tasks and activities for inclusion in the project schedule.

Any way they are applied, user stories and story cards are a useful tool for project managers to have in project planning and development. They provide a structured way to consider project features, activities, and stakeholder groups.