With over 40 years of project management experience I can’t help but conclude that despite the fact that projects are supposed to be finite efforts,

there are some projects that will never die. After a while they take on a life of their own even though no one remembers why the project is being done. It has become institutional. With the exception of those projects all projects follow a cycle of birth, maturation, and death just like any biological process or product life cycle. Up to the time of their birth (a.k.a. approval) projects are in a planning phase when the decision to undertake the project is made. Throughout their maturation phase (a.k.a. execution) projects are subject to change due mostly to random events whose likelihood was hopefully anticipated and planned but whose occurrence cannot be predicted. For all complex projects that maturation process includes the discovery, learning, and integration of functions and features into the solution. At some point in time the solution is deemed complete for the time and cost invested. The end of the project signals its death when the deliverables are produced and the project is completed successfully or acceptable deliverables are not produced and the project fails. Project success is measured by the deliverables having produced acceptable business value.

This is all well and good but the realities are often quite different. Are there active projects in your organization that are active only because their sponsor had the power and leverage to get them approved? If there ever was a valid business reason for the project, it is long since disappeared but the project hasn’t. Terminating a project is difficult especially because of the impact on the sponsor and the reputation of the client.

Declaring a project a failure and then terminating it is often not as clear a decision as one might think. Failure is a temporal decision. Take for example the case of the sticky note. The project that produced the glue was declared a failure because the glue did not have the physical properties needed. The project results sat on the shelf for over 7 years until an application for the glue was identified – result the Post-It Note. So one man’s failure may be another man’s success. If the project was to cure melanoma and instead delivered a successful tanning lotion that totally prevented sunburn, was the project a success or a failure? I mention this to you so that you will be cautious because in the complex project world failure is very difficult to define.

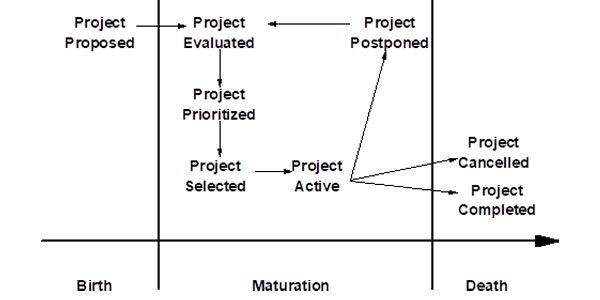

For the SMT each phase in the project life cycle requires continuous monitoring, adjustment, and stage-gate approval. These are described below. Figure 7.1 identifies the changing status of a project as it moves through the portfolio management life cycle. The portfolio management life cycle process is described in Chapter 8. For now it is sufficient to know that there are eight different stages that a project may be in during the portfolio life cycle. These are briefly described below as they align with each of the three phases in the project birth, maturation, and death processes.

Figure 1: The project birth, maturation and death life cycle

Project Birth Process

The project birth process begins with an idea and ends when the idea becomes an approved and funded project attached to the appropriate portfolio.

Project Proposed

All projects begin with an idea to address an existing problem or take advantage of a new business opportunity. It is the responsibility of the proposer or their staff to provide business validation that the proposed project makes good business sense.

The proposed project is documented with a one page Project Overview Statement (POS) and submitted to the appropriate portfolio to be evaluated regarding its alignment to the portfolio strategy and its suitability for support. The POS originated at Texas Instruments as part of its new product research and development process. I started using it in 1963 while an employee at Texas Instruments and have continuously adapted it to the project proposal process that I also developed. It is invaluable. The POS is a five-part document that contains:

Problem or Opportunity Statement

Every organization has a collection of known problems and untapped business opportunities. Several attempts to alleviate part of or the entire problem may have already been made but the problem persists. The POS gives proposers a way to relate their idea to a known problem and to offer a full or partial solution. If the problem is serious enough and if the proposed solution is feasible, further action will be taken. In this case, senior managers will request a more detailed solution plan from the requestor.

Untapped business opportunities abound. Technology fuels that. A statement that speaks to exploiting technology in order to improve an existing product or develop an entirely new one will certainly get the attention of the SMT.

Whichever the reason for the problem or opportunity statement, it must be written in the language of the business because it will be read by executives like you. So no techie talk allowed unless everyone who might have a reason for reading the POS speaks techie talk.

Project Goal

The second section of the POS states the goal of the project—what you intend to do to address the problem or opportunity identified in the first section of the POS. The purpose of the goal statement is to get the SMT to value the idea enough to read on. In other words, you should think enough of the idea to conclude that it warrants further attention and consideration. Several POSs might be submitted that propose projects addressing the same issue.

A project has one goal. The goal gives purpose and direction to the project. At a very high level, it defines the final deliverable or outcome of the project in clear terms so that everyone understands what is to be accomplished. The goal statement will be used as a continual point of reference for any questions that arise regarding the project’s scope or purpose.

Just like the problem or opportunity statement, the goal statement is short and to the point. The goal statement does not include any information that might commit the project to dates or deliverables that are not practical. Remember that you do not have much detail about the project at this point.

Project Objectives

The third section of the POS describes the project objectives. Think of objective statements as a more detailed version of the goal statement. The purpose of objective statements is to clarify the exact boundaries of the goal statement and define the boundaries or the scope of your project. In fact, the objective statements you write for a specific goal statement are nothing more than a decomposition of the goal statement into a set of necessary and sufficient objective statements. That is, every objective must be accomplished in order to reach the goal, and no objective is superfluous.

Identifying Success Criteria

The fourth section of the POS answers the question, “Why do we want to do this project?” It is the measurable business value that will result from doing this project. It sells the project to the SMT.

Whatever criteria are used, they must answer the question, “What must happen for us and the client to say the project was a success?” The COS will contain the beginnings of a statement of success criteria. Phrased another way, success criteria form a statement of doneness. It is also a statement of the business value to be achieved; therefore, it provides a basis for senior management to authorize the PM and the client to do detailed planning. It is essential that the criteria be quantifiable and measurable, and, if possible, expressed in terms of business value. Remember that the proposer is trying to sell their idea to the SMT.

No matter how you define success criteria, they all reduce to one of the following three types:

Increase revenue—As a part of the success criteria, the increase should be measured in hard dollars or as a percentage of a specific revenue number.

Avoid costs—Again, this criterion can be stated as a hard-dollar amount or a percentage of some specific cost. Be careful here because oftentimes a cost reduction means staff reductions. Staff reductions do not mean the shifting of resources to other places in the organization. Moving staff from one area to another is not a cost reduction.

Improve service—Here the metric is more difficult to define. It’s usually some percentage of improvement in client satisfaction or a reduction in the frequency or type of client complaints.

These criteria are often recognized by the name “IRACIS.”

The best choice for success criteria is to state clearly the bottom-line impact of the project. This is expressed in terms such as increased margins, higher net revenues, reduced turnaround time, improved productivity, a reduced cost of manufacturing or sales, and so on. This is the criteria on which the SMT will approve the project for further consideration and funding.

The SMT should look at the project’s success criteria and assign business value to the project. In the absence of other criteria, this will be the basis for the decision about whether to commit resources to complete the detailed plan or not.

Advertisement

[widget id=”custom_html-68″]

Assumptions, Risks, and Obstacles

The fifth and final section of the POS identifies any factors that can affect the outcome of the project and that should gain your attention as a member of the SMT. These factors can affect deliverables, the realization of the success criteria, the ability of the project team to complete the project as planned, and any other environmental or organizational conditions that are relevant to the project. The proposer wants to share anything that can go wrong and that the SMT might be able to favorably impact.

The project manager uses the assumptions, risks, and obstacles section to alert the SMT to any factors that may interfere with the project work or compromise the contribution that the project can make to the organization. The SMT may be able to neutralize the impact of these factors. Conversely, the project manager should include in the project plan whatever contingencies can help reduce the probable impact and its effect on project success.

Do not assume that everyone knows what the risks and perils to the project will be. Planning is a process of discovery about the project itself as well as any hidden perils that may cause embarrassment for the team. Document them and discuss them.

Attachments

Even though I strongly recommend a one-page POS, some business processes call for a longer document. As part of their initial approval of the resources to do detailed project planning, the SMT may want some measure of the economic value of the proposed project. They recognize that many of the estimates are little more than an order-of-magnitude guess, but they will nevertheless ask for this information. I have seen the following two types of analyses requested frequently:

- Risk analysis

- Financial analysis

The following sections briefly discuss these analysis types.

Risk Analysis

In my experience, risk analysis is the most frequently used attachment to the POS. In some cases, this analysis is a very cursory treatment. In others, it is a mathematically rigorous exercise. Many business-decision models depend on quantifying risks, the expected loss if the risk materializes, and the probability that the risk will occur. All of these are quantified, and the resulting analysis guides management in its project-approval decisions.

In high-technology industries, risk analysis is becoming the rule rather than the exception. Formal procedures are established as part of the initial definition of a project and continue throughout the life of the project. These analyses typically contain the identification of risk factors, the likelihood of their occurrence, the damage they will cause, and containment actions to reduce their likelihood or their potential damage. The cost of the containment program is compared with the expected loss as a basis for deciding which containment strategies to put in place.

Financial Analyses

Some organizations require a preliminary financial analysis of the project before granting approval to perform the detailed planning. Although such analyses are very rough because not enough information is known about the project at this time, they will offer a tripwire for project-planning approval. In some instances, they also offer criteria for prioritizing all of the POS documents that senior management will be reviewing. At one time, IBM required a cursory financial analysis from the PM as part of the POS submission. Following are brief descriptions of the types of financial analyses you may be asked to provide.

Feasibility Studies

The methodology to conduct a feasibility study is remarkably similar to the problem-solving method (or scientific method, if you prefer). It involves the following steps:

- Clearly define the problem.

- Describe the boundary of the problem—that is, what is in the problem scope and what is outside the problem scope.

- Define the features and functions of a good solution.

- Identify alternative solutions.

- Rank alternative solutions.

- State the recommendations along with the rationale for the choice.

- Provide a rough estimate of the timetable and expected costs.

The PM will be asked to provide the feasibility study when senior management wants to review the thinking that led to the proposed solution. A thoroughly researched solution can help build your credibility as the project manager.

Cost and Benefit Analyses

These analyses are always difficult to do because you need to include intangible benefits in the decision process. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, things such as improved client satisfaction cannot be easily quantified. You could argue that improved client satisfaction reduces client turnover, which in turn increases revenues, but how do you put a number on that? In many cases, senior management will take these inferences into account, but they still want to see hard-dollar comparisons. Opt for the direct and measurable benefits to compare against the cost of doing the project and the cost of operating the new process. If the benefits outweigh the costs over the expected life of the project deliverables, senior management may be willing to support the project.

Breakeven Analysis

This is a timeline that shows the cumulative cost of the project against the cumulative revenue or savings from the project. At each point where the cumulative revenue or savings line crosses the cumulative cost line, the project will recoup its costs. Usually senior management looks for an elapsed time less than some threshold number. If the project meets that deadline date, it may be worthy of support. Targeted breakeven dates are getting shorter because of more frequent changes in the business and its markets.

Return on Investment

The ROI analyzes the total costs as compared with the increased revenue that will accrue over the life of the project deliverables. Here senior management finds a common basis for comparing one project against another. They look for the high ROI projects or the projects that at least meet some minimum ROI.

A project that does not meet the alignment criteria may be either rejected out of hand or returned to the proposing party for revision and resubmission. Projects that are returned for revision generally need minor revision and following the suggested revisions should meet the alignment criteria.

These four financial analyses are common. Their purpose is to help the financial analysts determine the risk versus reward for the proposed project.

As a member of the SMT you have the power of rank at your disposal. So my first caution to you is don’t abuse your power by forcing your project idea into the portfolio. Staff below you in the organization has a difficult time saying no or pushing back on your idea. If your idea is valid from an expected business value perspective, sell it on its own merits not on the power of your office. Clogging the process with frivolous ideas is a waste of time and resources and just adds confusion to a challenging portfolio management process.