This article first appeared in the May 1, 2008 Business Analyst Times

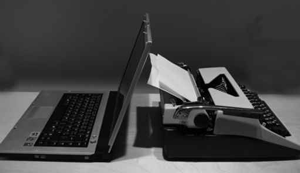

My life as a project manager (PM) began in 1963 at Texas Instruments at about the time IBM announced System 360. It was a landmark event in the history of computing and little did I know at the time but it was also the wakeup call that a revolution was about to take place. It was a revolution that we weren’t ready for. If I remember correctly I ran projects but was called a systems consultant. I don’t recall anyone in my industry carrying the title project manager.

There was very little in the way of tools, templates and processes to support me. The only software that I knew about was an old IBM1130 program that I think was called Process Control System. One of my friends in the building construction trade introduced me to it and I thought I was now king of the hill. PMI wouldn’t arrive on the scene until 1969.

As for the business analyst (BA) they weren’t around, at least not by that name. What we did have were computer professionals that were called systems analysts. They were the mystics from the IT Department who could talk to a businessperson about what they wanted, retreat into their space to concoct a solution, emerge to tell the programmers what to build and then hope for the best. Few clients were satisfied with the results but they weren’t involved enough to know what to do about it. Life was tough in those early days of project management and systems development. Clients were kept at arm’s length and only got involved when it was time to sign a document under the threat of a project delay if they didn’t sign. Every one of my colleagues, including myself, was looking for silver bullets.

Fast forward to 2008. The systems development landscape is more mature as are the life cycles employed. We have linear, incremental, iterative, adaptive and extreme projects. In less than 40 years PMI has grown to over 250,000 members worldwide. It is the de facto professional society for PMs. IIBA, launched in 2003, is just getting started and has a membership of over 4,000 worldwide. Size differences aside the two organizations have a lot in common and a lot to gain through collaboration and joint ventures.

The major area of overlap is requirements gathering and management. Both the PM and the BA face the same challenges here. Even under the best of circumstances it is very difficult, if not impossible, to identify and document complete requirements. The reasons are many and well known to both professional groups. Underlying it all is the need for more collaborative efforts.

The next area of overlap is process improvement. In the world of the PM and their management this means applying some variation of the Capability Maturity Model and continuous project management process and practice improvement. For the BA this means business process improvement projects and that means having effective project management methodologies.

The next area of overlap is the skill and competency profile of the effective PM and the effective BA. The two profiles are virtually identical. Some have posited that we really don’t need both types assigned to the same project. We could certainly debate that point of view but, if present trends continue, I would argue that a single person, whatever label you choose to use, will soon be sufficient. In other words the BA should have the requisite skills and competencies to be an effective PM and the PM should have the requisite skills and competencies to be an effective BA. They will have morphed into one professional. Lacking an appropriate name right now, I’ll refer to this single professional as a BA/PM. We are not too far away from that day.

The next area of overlap is the processes, tools and templates that both professionals follow. Again they are virtually identical at the concept level.

I could go on but I think you get the picture. I am led to the conclusion that the support of both the PM and the BA should lie in a single organizational entity that I am going to call the Business Project, Program, Portfolio and Process Office or BP4O for short. Please excuse my taking liberties with the multiple use of “P”. I do that for good reason. PMs have had the Project Management Office (PMO) under various names for a number of years. The BA has not had a similar support organization. Recently I have seen Communities of Practice (COP) and Centers of Excellence (COE) emerging for the BA, but these are more voluntary forums for the BA to network and exchange ideas with their peers than an organized business unit. There is no valid argument that can be given for not expanding the PMO to embrace the BA. That is what I am calling the BP4O and that is the focus of the remainder of this article.

The World Class BP4O

On the surface the world class BP4O won’t seem much different than the traditional PMO. The world class BP4O offers an expanded portfolio of support functions as compared to the typical PMO but if you look under the hood, you will see that I am proposing that there be a significant difference. In organizations that see the handwriting they see that project management, program management, portfolio management and business process management are all converging on a single strategic role with enterprise-wide scope. The world class BP4O that I envision is a central participant in that role. It helps define strategy and through its infrastructure provides for the enablement of that strategy too. And so here is my first shot at a definition of the world class BP4O.

Definition of the World Class BP4O

The world class BP4O is an enterprise-wide organizational unit that helps formulate and fully supports the strategic, tactical and operational initiatives of the enterprise. The world class BP4O is characterized by:

- Led by the VP BP4O who has a voting seat at the strategy table

- Fully participates in the formation and approval of the business plan at all levels

- Establishes the processes for and monitors the performance of the project portfolio

- Has authority and responsibility to set priorities and allocate resources to projects

- Establishes standards for the tools, templates and processes used by BAs and PMs

- Monitors compliance in the tools, templates and processes used by BAs and PMs

- Establishes an integrated BA/PM position family with defined career paths

- Provides a complete program (training and human resource management) for the professional development of all BA/PMs

- Assures that the skill and competency profile of the BA/PM staff is sufficient for the realization of the project portfolio

- Allocates BA/PMs to the approved portfolio of projects

- Offers a full range of support services to executives, sponsors and project teams

- All BA/PMs have an approved professional development program.

- Performance metrics:

- The project management and business process methodologies are assessed at CMMI Maturity Level 5

- On average the practice maturity level is at least CMMI Maturity Level 3

- The project failure rate is less than 10%

As you can see the VP BP4O is an integral part of the enterprise from the strategy formation level to tactical planning to execution at the operational level. It is that unit’s responsibility to make the most effective use of the enterprise’s human resources towards the realization of the business plan.

Mission of the World Class BP4O

To provide a comprehensive portfolio of strategic, tactical and operational support services to all project teams, sponsors and executives in order to assure the delivery of maximum business value from the project portfolio.

Objectives of the World Class BP4O

- Define a project life cycle with stage gate approvals.

- Design, develop, deploy and support a comprehensive portfolio of tools, templates and processes to effectively support all projects.

- Design and deploy a project review process to support project teams and monitor compliance to established standards and practices.

- Establish a project portfolio management process to maximize the business value of project investments.

- Establish a decision support system and dashboard to support executive management’s project decisions and provide for the timely monitoring of the project portfolio status.

- Design, develop, deploy and support a comprehensive HR Project Management System.

- Design, develop, deploy and support a continuous process improvement program for the BP4O.

Organizational Structure of the World Class BP4O

The only structure that makes sense to me is one where the BA/PMs are close to their client groups. That structure is what I call the “Hub & Spoke. At the Hub we have the enterprise level unit that is responsible for policy, process and staff development. At the Spokes are the various divisions and departments with their own staff of BA/PMs. They might establish tools, templates and processes specific to their needs but in compliance with the enterprise policies and processes.

Staffing of the World Class BP4O

There are five staffing models that come to mind:

- Virtual BP4O

The Virtual BP4O does not have any BA/PMs assigned to it. Instead they are deployed throughout the enterprise where they are assigned on an as needed basis by their organizational unit. These are not fulltime project managers but are professionals in other disciplines who have project management skills and competencies as part of their toolkit.

The BP4O staff consists of a manager and one or more assistants who support BA/PMs as required. They may be BA/PMs but that is not necessary. The important thing is that this staff has the necessary expertise to provide the support needed. The support services may span the full list but are often quite restricted because of staff limitations.

- BA/PMs are assigned to the BP4O on a rotating basis

This is an excellent model for deploying the BA/PM methodology, skills and competencies throughout the organization. In this model BA/PMs from the business units are temporarily assigned to the BP4O as a sabbatical from being on the firing line too long. A sabbatical might last from 3-6 months during which time they might conduct a specific process improvement project or simply act as mentor and coach to other BA/PMs.

- BA/PMs assigned to the BP4O

In this structure the BP4O BA/PMs manage critical mission or enterprise-wide projects. Usually not all BA/PMs report to the BP4O. There will be several who are assigned to business units to work on less comprehensive projects for their unit.

- BA/PMs assigned at the division level

BA/PMs assigned at the division level work on division-wide projects. These may be projects that span two or more departments.

- BA/PMs assigned at the department level

Same as the division level except they are assigned within a department and only work on projects contained within their department.

Summary

This article is an opening gambit for me. My hope is to expand on some of the ideas expressed above in future articles. I hope that this article has provided food for thought and that you will take the time to let us have your comments.

Robert K. Wysocki, Ph.D., has over 40 years experience as a project management consultant and trainer, information systems manager, systems and management consultant, author, training developer and provider. He has written fourteen books on project management and information systems management. One of his books, Effective Project Management: Traditional, Adaptive, Extreme,3rd Edition, has been a best seller and is recommended by the Project Management Institute for the library of every project manager. He has over 30 publications in professional and trade journals and has made more than 100 presentations at professional and trade conferences and meetings. He has developed more than 20 project management courses and trained over 10,000 project managers.

With this Project Times, we’re running the first in a series of articles from Business Analyst Times by Bob Wysocki that asks the question, Is it Time for the BA and the PM to Get Hitched? He weighs in with the view that there is a lot of overlap between requirements gathering and management and wonders if the BA and the PM roles shouldn’t be rolled into one. It caused much controversy amongst the Business Analyst Times readers, and we’d love to hear what you think from a project manager’s standpoint. We have added a dedicated BA/PM discussion forum topic here.

With this Project Times, we’re running the first in a series of articles from Business Analyst Times by Bob Wysocki that asks the question, Is it Time for the BA and the PM to Get Hitched? He weighs in with the view that there is a lot of overlap between requirements gathering and management and wonders if the BA and the PM roles shouldn’t be rolled into one. It caused much controversy amongst the Business Analyst Times readers, and we’d love to hear what you think from a project manager’s standpoint. We have added a dedicated BA/PM discussion forum topic here.