Doing What You Can to Change the Unacceptable

Don’t underestimate your power to make positive change. Angela Davis, a passionate activist, is quoted as saying:

“I have given up on accepting the things I cannot change.

I aim to change the things I can’t accept.”

As project managers we are often faced with unacceptable realities that get in the way of project and career success.

Take for example the situation in which meeting a deadline relies on resources promised by a functional manager to be available at a specified date. The resources do not show up because they are assigned to another project and won’t be available for weeks. To make matters worse, the situation is often repeated, and functional managers are never held accountable. The organization holds the PM responsible for getting the project done on time, no matter what. But in reality, most projects are late, and no-one is ever fired for it. Everyone accepts the fact that schedules cannot be trusted. Clearly there is some dysfunction.

There are other examples of unacceptable situations, your boss or co-worker is abusive or incompetent, your sponsor or client chronically has irrational expectations and will not listen to reason, etc.

With a fixed mindset, you can believe that nothing can be done about it. You might be thinking “It’s always been like this and it always will be.” or “I can’t do anything about it, its above my pay grade.” If everyone is thinking that way the situation won’t change. If everyone misunderstands the advice to accept things as they are, things will not change.

Change is possible with a shift to a realistic understanding and a growth mindset that realizes that learning and change are possible. Accepting things as they are does not mean keeping them that way. It simply means that since you can’t change the present moment or the past, the best you can do is to accept what is and what was. The future is subject to change if you apply the courage and skill to act effectively.

Passion and Equanimity

When we aim to change the things we can’t accept, we are faced with the paradox of equanimity and passion. They are both required.

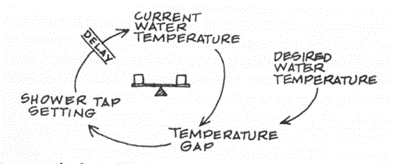

Equanimity is mental calmness and balance regardless of external circumstances. It is accepting that passionate action and unphased acceptance coexist. With equanimity we have the presence of mind to accept what is, analyze what got it that way, plan to do something about it, act, and accept what happens. Whatever happens, we repeat the process – accept, plan, act, accept. Progress is an ongoing process.

In our example, let’s say the analysis uncovers that functional managers want to honor their commitments but are faced with demands from multiple projects and their sponsors that cause them to over commit. A rational plan to correct the situation would be to establish an effective portfolio management process which moderates the flow of projects, recognizing the interrelationships between functional resource availability across multiple projects. To project management professionals, it seems a no-brainer. But creating and sustaining a portfolio management process in an immature PM environment is not easy.

If formal portfolio management doesn’t happen there is still hope. There is always something to do, including doing nothing. Your options range from accepting the status quo to changing jobs. In between are options like grass roots cooperation among managers as resource demands change, multi-project monitoring at a PMO level, patiently and skillfully petitioning executives for portfolio management, and more.

This is where passion comes into play. Passion is a strong feeling of enthusiasm about something. If there is a passionate desire to correct the situation, then it is more likely to happen. And equanimity provides the best platform for making the change you want.

Advertisement

[widget id=”custom_html-68″]

Set and Setting

An often-overlooked aspect of making and managing change in our work environment is personal feelings. On a practical, analytical, unemotional level we can come up with the means to make change. If we do nothing or if what we do doesn’t improve the situation, there are feelings – anger, frustration, fear, despair, a loss of passion, etc.

On a personal level self-awareness and self-management, the two principal parts of emotional intelligence must be applied to enable you to change the things you cannot accept. On one extreme of the practical options is doing nothing, accepting the status quo.

If you do absolutely nothing, your feelings will not change. They will get stronger. Your anger might turn to depression. Your performance might suffer. So, you do something, you change your mindset. Environment (setting) and mindset (the way we think, our beliefs and mental models) determine the way we feel and our behavior.

We Can Change Our Mind

While we can change our environment – the organization culture, stakeholders, etc. – our ability to do so is limited. On the other hand, we have far more control of our mindset (though sometimes it doesn’t seem so). Changing the mindset begins with adopting an attitude of acceptance and letting go.

If we accept that we are in an unacceptable situation and we can’t change it, we can leave – ask for a transfer, find a new job, retire. If we choose to stay, for whatever reason, we have the difficult task of avoiding letting the situation lead to debilitating emotional reactions, like the anger and despair mentioned earlier. That is where a mindset that includes the belief that it is possible to be equanimous and optimally well in any situation is essential.

Apply mindfulness and emotional intelligence to remind yourself that you can change the way you think and feel, that everything changes, and that you can accept the status quo and do what you can to change your setting. This approach leads to a sense of personal control and hope for improvement. It is the theme of my latest book – The Peaceful Warrior’s Path: Optimal Wellness through Self-Aware Living and my first book, The Zen Approach to Project Management.

Related articles:

Learn from the Past to Perfect Performance

Making the Impossible Possible

Practical Perfectionism and Continuous Improvement