Shutdown Project Management

I’ve had my attention on an aspect of project management that is absolutely fascinating and that I haven’t spent much time on in the last five or six years. Shutdown/Turnaround project scheduling is, in many ways, the epitome of the project scheduling paradigm and, like everything else in the project management industry, it too has evolved in recent history.

For most of us, when we think of project schedules, we think of building something. The end result is something that didn’t exist before the project started. Perhaps it’s a building or a spacecraft or a software system or a new drug. Shutdown/Turnaround projects are quite different. In every major manufacturing plant, there is some maintenance which can be accomplished while the plant is running and some maintenance which can only be accomplished when the plant is not. For example, it’s common for a major pulp and paper or chemical plant or steel mill to shut down completely once or twice per year in order to refurbish those significant elements of the plant which can’t be updated otherwise. The goal becomes to go from shutdown to start up as quickly as possible; to turn the plant around from stopped to started. Hence the term shutdown and/or turnaround for this kind of project.

A major shutdown for such a plant might last anywhere from four to six days. Sometimes a plant requires a less significant pause in operations which might last only one day. The value of the project is measured by opportunity cost. This means we measure the value of the material that the plant cannot produce due to its being closed. In some plants that’s often $100k to $200k per hour. Yes, $100,000 to $200,000 per hour. That’s scheduling pressure and therein lies a very different kind of project management.

A shutdown planning team is typically a small close-knit group of highly trained schedulers who will prepare all the schedules, update them as need be and prepare the foremen and contractors with whatever they need to get their work accomplished as quickly as possible.

This kind of project management carries a number of idiosyncrasies that we aren’t likely to find in high tech project management or bio research project management. Here are some:

Notice

When we think of white-collar project management, we think of an orderly progression towards the start of the project. We get funding. We get an executive sponsor. We make a project charter. We organize our project team. We prioritize our work, and so on. A shutdown schedule is often planned for months in advance, but the actual start of the project can come up on you without notice. That can happen if there’s an emergency shutdown due to equipment failure. I remember meeting with a number of shutdown scheduling managers a few years ago. One scheduling manager from the nuclear industry was bemoaning how he might get only six weeks notice for a shutdown project on his nuclear power plant. A scheduling manager from a chemical plant responding with a note of disbelief “Six weeks!” he said. “Do you know what notice I get? I see a bunch of guys running by the door to my office and I say ‘Hey guys, where are you going?’ and they respond ‘We just shut down’. That’s the notice I get.”

Sub-contracting

When the value of your project is being measured in the hundreds of thousands of dollars per hour, you don’t quibble over finding the right people to do the work. Also, the project will only last a few days out of the year, so every shutdown project I’ve ever been a part of had a huge sub-contracting aspect to it. Literally hundreds of people might be brought in from dozens of sub-contractors over a tiny amount of time. These personnel must all be managed. The contractors must be rigidly controlled to ensure they go to the right place and are ready at the right time and, last but not at all least, these hundreds of people who are not used to being in this plant full time must be safe.

Safety

We often have safety concerns in project management but in a shutdown environment it’s more prevalent a problem. The vast majority of personnel will be on the site for only a few days, some of them for the first time. A major industrial plant is a dangerous place even when it’s not operating and all these people need to be kept safe.

Resource Leveling

These days in enterprise project management we tend to talk about Resource Capacity Planning to see what additional work we could take on. That’s not the case here. When there is a shut down, there is no other work that will contend for these resources. The CEO himself can be called upon if that’s required in order to get the job done. So there is no multi-project resource contention. There is also no limit to the number of resources I can contract. What there is, are the physical limitations of resources on the plant site and for each piece of equipment. You might have a task to rewire an electrical room and, in theory, you could do it with 20 electrical engineers. However, the room can’t fit more than three people so your resource leveling has to contend with that. We tend to think of resource scheduling in a shutdown not just of personnel but also equipment, such as heavy lifting cranes and physical space restrictions. It’s a significant resource management challenge.

Per-minute Planning

In a high-tech type of project, we think of scheduling in person-days or person-weeks. In a shutdown, we tend to think in quarter-hour increments or even down to the minute. Knowing that a task can be complete at 6:30 instead of 7:00 can have an enormous impact to the overall schedule. After all, that half hour is worth $50,000 to $100,000!

Lead Time Items

One of the most disastrous things that can happen on a shutdown is to get to a critical task only to find that something that takes days or weeks to order isn’t there. I remember one of our staff working on a shutdown. He was there a week or two in advance and, the day before the scheduled shutdown, a contractor slipped and the result was catastrophic. A tool touched the wrong thing on a power transformer which promptly spectacularly disintegrated. This transformer was not supposed to be replaced and there was no replacement on site. The transformer company half-way across the country had to be immediately contracted to create a new transformer to conform exactly to the one that had been destroyed. Price was no object. A special train was contracted to transport the device to the site in the middle of the night. In the meantime, temporary generators were rushed into the site so contractors could continue working. Total delay: approximately 24 hours; meaning over $2 million dollars (remember, we measure the cost as the value of what can’t be produced in the time the plant is closed).

If you’re involved in such projects and in creating a project management environment, there are a number of places to look for where you can generate value for your organization. Here are three:

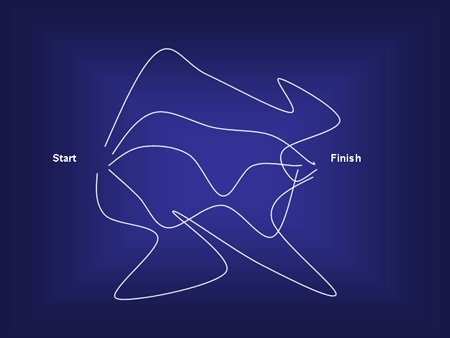

Reiterative Planning

Unlike some projects, a shutdown project is very repetitive. But this gives us a unique opportunity to realize some significant efficiencies. Several years ago, I worked with a planning group which worked over a two year period to analyze project schedules for their main shutdown. They compared the plans to the “as-built” schedule to compare what was planned to what actually happened. They looked for any level of inefficiency in the schedule to see where the plan for the next shutdown could be made shorter. In the end, they reduced the planned shutdown schedule from 6.6 days (which had been believed to be the shorted theoretical time) to 4.4 days, a savings of over $2,000,000 per shutdown!

Document Management

Many organizations have digitized plant maintenance and equipment documentation systems so they can be instantly available from any terminal in the plant. The time that used to be taken to run from one end of the plant to the other, in order to go through a series of file cabinets to find a maintenance guide should be a thing of the past. If you can link these documents to the tasks in the online schedule, then finding information faster and easier can realize big efficiency gains

Contractor Updating

With web-based systems, contractors can now participate in systems to update the schedule as

it’s happening on the shop floor, or immediately following the shift in which the work is done. It’s essential to collect the actual progress information, as quickly as possible, while the schedule is underway so that the schedule can be updated for the next shift. Also, one major aspect of a shutdown that is an enormous undertaking is figuring out, once it’s done, what contractor did what work and reconciling the invoices from the contractors with the work that was accomplished. Both of these goals can be helped with a contractor timesheet system that is linked directly into the schedule.

The lessons we learn from shutdown/turnaround planning can be of benefit to everyone but, what I think is most valuable, is realizing that project management isn’t one big homogeneous set of practices. Trying to blindly apply the same practices we’d use for one kind of project management into a shutdown might have disastrous consequences. For each project management environment you are confronted with, you must look at it for the particular business challenges it represents, and bring forward the tools that are appropriate to those challenges.

Chris Vandersluis is the founder and president of HMS Software based in Montreal, Canada. He has an economics degree from Montreal’s McGill University and over 22 years experience in the automation of project control systems. He is a long-standing member of both the Project Management Institute (PMI) and the American Association of Cost Engineers (AACE) and is the founder of the Montreal Chapter of the Microsoft Project Association. Mr. Vandersluis has been published in numerous publications including Fortune Magazine, Heavy Construction News, the Ivey Business Journal, PMI’s PMNetwork and Computing Canada. Mr. Vandersluis has been part of the Microsoft Enterprise Project Management Partner Advisory Council since 2003. He teaches Advanced Project Management at McGill University’s Executive Institute. He can be reached at [email protected].