Developing Leaders of Complex Projects

This is the second article in the series describing the unique nature of complex projects and proposing an approach to manage project complexities. The first article described the characteristics of highly complex projects. A new model, the Project Complexity Model, was introduced. The model is used to diagnose the level of complexity of a particular project, or projects, within a program. Once the project complexity profile is determined, project leaders are urged to apply complexity thinking to make managerial decisions about the project.

It is clear that projects sometimes fail because of an inappropriate match of project leadership capability to the level of project complexity. The project manager, business analyst, lead IT architect and developer, and business visionary are four critical project leadership positions. Once the project complexity has been understood, this article makes the case for organizations to use this vital information to make project leadership assignments.

As organizations depend more and more on project outcomes to achieve their strategic goals, they are developing career paths for their project leadership positions, including project managers, business analysts, lead technologists (architects and developers), and business visionaries. Organizations that are undergoing pivotal transitions require leaders who exhibit characteristics and follow a career path that differs in certain respects that of traditional project leaders. Complexity thinking can assist organizations in identifying and developing these leaders.

Traditional Project Leader Career Path

The traditional project leader career path starts with entry-level associates who are

critical, complex projects (see Table 1).

|

Level

|

Proficiency

|

Responsibilities

|

Competencies

|

|

Strategic

|

Ability to perform strategic tasks with minimal direction

|

Lead large, highly complex projects

|

§ Business and IT strategy

§ Program and portfolio management

§ Systems engineering, BPR, six sigma

§ Enterprise architecture

§ Business case development

|

|

Senior

|

Ability to perform complex tasks with minimal coaching

|

Lead moderately complex projects

|

§ Business and IT domains

§ Advanced project management and business analysis

§ Systems engineering, BPR, six sigma

§ Requirements engineering

|

|

Intermediate

|

Ability to perform simple to moderately complex tasks with minimal assistance

|

Lead small, independent projects

|

§ Business or IT domain

§ Fundamentals of project management and business analysis

§ Quality management

§ Facilitation and meeting management

§ Basic requirements modeling

|

|

Associate

|

Ability to perform simple tasks with assistance

|

Support intermediate and senior PM/BAs

|

§ PM/BA principles

§ BPR, six sigma principles

§ Business writing

|

Table 1. Traditional Project Leader Career Path

Emerging Complex Project Leadership Career Progression

The Australian Competency Standard for Complex Project Managers proposes a new four-tiered career path:

- Project manager

- Traditional senior project manager

- Program manager

- Complex project manager

While this structure is not yet fully accepted in the project management community, it is certainly food for thought as we consider the competencies needed to manage complex projects successfully. The standard also proposes certification levels for traditional and complex project managers (see Table 2) and describes four competency levels for each action in the workplace (see Table 3).1

|

Traditional

|

Complex

|

|

Project Manager

|

Senior Project Manager

|

Program Manager

|

Member

|

Fellow

|

Table 2. Complex Project Manager Certification Levels

|

Traditional

|

Complex

|

|

Actions in Workplace

|

Project Manager

|

Senior Project Manager

|

Program Manager

|

Member

|

Fellow

|

|

Develops vision statement, values charter, code of conduct, and mission statement

|

D

|

D

|

P

|

C

|

L

|

|

Maps stakeholder alignment/differences over the project life cycle

|

D

|

D

|

P

|

C

|

L

|

Table 3. Complex Project Manager Competency Model

Key:

D – Development

P – Practitioner

C – Competent

L – Leader

For each action in the workplace, certification levels are defined as follows:

- Development. The project manager applies the competency under direct supervision.

- Practitioner. The project manager applies the competency without the need for direct supervision, but within the bounds of standardized processes, procedures, and systems.

- Competent. The project manager applies the competency without the need for direct supervision, provides direct supervision of the competency for others, and mentors development of the competency in others.

- Leader. The project manager provides professional leadership in the competency, leads in the design of processes, procedures, and systems, and has the ability to use the competency flexibly and creatively.

Successful Leadership Characteristics for Organizations Undergoing Pivotal Transitions

As we work to identify and develop leaders of complex projects, it is helpful to examine a model for extraordinary organizational leadership presented by Jim Collins. Collins provides us with researched-based information on the characteristics of business leaders whose companies are exceptionally successful during pivotal transition periods; these characteristics are also relevant to project leaders who are successful in leading complex business transformation projects.

Collins describes exceptional leaders as very ambitious but also very humble. Their ambition is first for the organization rather than for themselves, and their goal is to leave the legacy of a successful enterprise. Characteristics of these leaders, which Collins refers to as “Level-5 Leaders,” include a compelling personal humility coupled with an unwavering resolve that he calls professional will.2 Collins describes a leader with personal humility as someone who:

- Demonstrates a compelling modesty, virtually shunning public praise

- Acts with quiet, calm determination

- Channels ambitions into the company; identifies and mentors successors for even greater success

- Attributes success to others.

A leader who exhibits professional will:

- Creates superb results

- Demonstrates an unwavering resolve to do whatever it takes to produce the best long-term results for the enterprise

- Sets the standard of building an enduring great company

- Attributes responsibility for poor results to himself.

We submit that leaders of complex projects should strive to become Level-5 Leaders, doing whatever it takes to produce the best long-term results. We have adapted Collins path to Level-5 Leadership to depict the journey to becoming a complex project leader (see Table 4).

|

Leadership Level

|

Leadership Characteristics

|

|

Level 1

|

HIGHLY CAPABLE INDIVIDUAL

Contributes to project success through individual expertise, talent, knowledge, skills, and good work habits.

|

|

Level 2

|

CONTRIBUTING TEAM MEMBER

Contributes individual capabilities to the achievement of business objectives and works effectively with others.

|

|

Level 3

|

COMPETENT PROJECT LEADER

Organizes people and resources toward the effective and efficient pursuit of business objectives.

|

|

Level 4

|

EXCEPTIONAL PROJECT LEADER

Commits to vigorous pursuit of a clear and compelling project vision, stimulating higher performance standards with a track record of project success.

|

|

Level 5

|

COMPLEX PROJECT LEADER

Brings about business transformation in pursuit of new business strategies through personal and professional leadership.

|

Table 4. Complex Project Leader Development Model Adapted from Jim Collins’ Level-5 Leadership Hierarchy

Using Complexity Thinking to Assign Complex Project Leaders

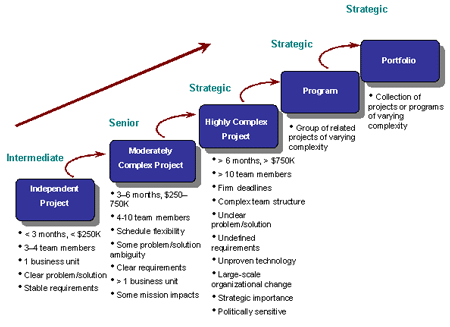

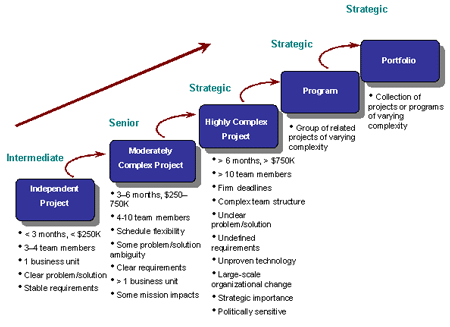

To make the most appropriate project leadership assignments, project complexity must be considered by resource managers. Exhibit 1 maps the generic career levels presented earlier with the project profiles contained in our Project Complexity Model presented in the first article in this series. As depicted, strategic-level leaders are needed to manage not only highly complex projects, but programs (groups of projects managed in a coordinated way to obtain greater benefits) and portfolios (collections of projects or programs managed together to achieve strategic goals) as well.

Exhibit 1. Project Leadership Capability Maturity Model

Summary

Organizations are recognizing that complex projects require an exceptional leadership team of experts and are developing career paths for their project leadership positions—project managers, business analysts, lead technologists (architects and developers), and business visionaries accordingly.

Based on the project profile diagnosed using the Project Complexity Capability Maturity Model, organizations undergoing pivotal transitions can apply complexity thinking when considering assignments for complex project leaders. Projects need no longer fail because the key project leadership positions are filled with individuals who are not sufficiently skilled and practiced to make the appropriate managerial decisions about the project, build and sustain a high-performing project team, and adapt to changes as the project unfolds.

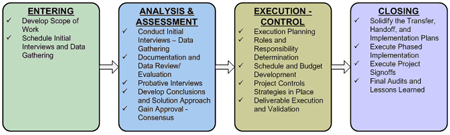

Look for the third article in this series in the next issue, describing how the project leadership team uses the Project Complexity Model to select the most appropriate project cycle.

Endnotes

1. Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Defense), College of Complex Project Managers and Defense Materiel Organisation, Competency Standard for Complex Project Managers, 2006. Public Release Version 2.0. Online at https://www.projecttimes.com/wp-content/uploads/attachments/Complex_PM_v2.0.pdf (accessed January 2008), pp. 17, 18.

2. Jim Collins, Good to Great, Why Some Companies Make the Leap…and Others Don’t, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2001, p. 20.

Note: Much of the information in this article has been previously published in other forms, including the book published by Management Concepts in 2008 entitled: Managing Project Complexity: A New Model.

Kathleen Hass, PMP, is the Senior Practice Consultant for Management Concepts, Director at Large, Chapter Governance Committee chair and contributing author of the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge for the International Institute of Business Analysis (www.theiiba.org). Kitty has more than 25 years of experience in project management and business analysis, including project office creation and management, business process re-engineering, organizational development, software development, technology deployment, project management training, mentoring and team building. For more than a quarter of a century, Management Concepts, whose mission is to unleash the potential of people, has provided quality training and performance improvement solutions for the mind at work. For further information, please call 1-703-790-9595 or visit the company website at www.managementconcepts.com.