Estimation can be one of the most difficult parts of a project. Important questions must be asked in order to form the right figures and plans. How long will the project take? How many resources will it consume? Consultants may also ask the following question: What is the appropriate amount to bid on this project? These questions are not easy to answer at the outset when one generally has only a vague idea of what will be required throughout the project.

The good news is that there is a fairly simple way to improve project estimation and, consequently, the bidding process. Most people do not realize that the requirements creation process can lend insight into the length and scope of a project. Let me give you an example of how this method works and then explain how you can implement it within your own company.

The Story

Back in 1992, I was working for a consulting company named The Kernel Group (TKG). During this time, I was put in charge of porting Tivoli’s software from Sun’s Solaris operating system to IBM’s AIX operating system. The project was to be done under a fixed bid, and consequently, we at TKG knew that estimating the effort required to port the code was of paramount importance.

I looked at the code with a coworker of mine, and he came to the conclusion that if Tivoli didn’t make the project hard for us in some unspecified way, we could port the million or so lines of code in about a weekend. I told him that he was nuts – that it would take at least a week, maybe even two. We jointly decided that we probably ought to call it three weeks just to be safe. We also decided, rather smugly, not to report our padding of the schedule to evil upper management.

As a result, evil upper management drastically expanded the project bid to $325,000, and my coworker and I thought that this was a ridiculously high price. We believed that we were gouging the customer and that they would never accept it.

Yet they did accept it, and once the project began, we proceeded to discover how truly terrible we as software engineers were at the task of project estimation. To make a long story short, the porting schedule expanded to exceed our original estimate and we consumed not only all of the $325,000, but a whole lot more on top of it.

The Formula

Now our consulting company was religious about tracking employee time on a per-project basis, and so we broke every project into phases: requirements/specification, design, coding, testing, debugging, documentation, training, etc. This project was no different in that respect; we broke it down into its respective phases as well.

Just before we started working on the project in question, I read a book called Practical Software Metrics for Project Management and Process Improvement by Robert B. Grady. (By the way, this is a truly fabulous book that I would highly recommend to anyone who is managing software development projects.) According to the book, one of Grady’s rules of thumb is that 6-8% of every software project is usually eaten up in the requirements/specification phase.

One of the conclusions that Grady comes to in his work is that you can use this fact to estimate total project size. In other words, if it took 60 hours to do the specification, that’s probably 6% of the job and the job will be 1000 hours. Following such logic, a six hour specification implies a 100 hour job. Since the specification always comes first in any project, you can get some pretty reliable estimates from this method alone. In fact, in my experience as both a programmer and the CEO of a software company, I have found it to be incredibly accurate and useful.

A second way to triangulate this project estimate is to ask experts in the area for their opinions – hopefully they will be better at project estimation than my coworker and I were that first time. A third way is to select an appropriate metric for estimation. For example, one could use line of code counts or function points in estimating the length and scope of software projects. For architecture projects, you might use number of pages in the drawings or square feet planned as similar analogies. Every project has some gross measure of its size that is available at the outset and can be used to plan the overall project in addition to this method I’ve described of tracking time against the earliest phases.

So back to the story. We really blew it on estimating and bidding on that first project for Tivoli, but when the next one came around, we had data on the portion of the overall project that the requirements phase had taken up. This allowed us to use Grady’s ratio to predict overall project size, and we found that on this second project, we came up with a very accurate project estimate. This worked very well for all of the subsequent fixed-cost consulting work we did for Tivoli.

Partially due to the strength of the solution and how well it ran on IBM’s AIX operating system, Tivoli was able to eventually sell their company to IBM for 743 million dollars in 1995.

For a consultancy that is doing fixed-cost projects, this concept of using the standard ratio of requirements phase to overall project length is a very powerful project estimation technique. It can eliminate erroneous bidding and its resulting costs, which is a major concern for such companies.

Accurate Bidding

Overbidding on a consulting job means that you won’t get the work in the first place, because the potential customer will give it to your competitor at a cheaper price. Underbidding, however, means you will win the deal and lose money. Neither situation is acceptable for businesses today, and yet, most consultancies do a poor job in this area. One way to make more precise bids is to use a key performance indicator, which is a tool used to measure progress towards a strategic business goal. For example, the number you want to minimize in this situation is defined by the formula [(E-A)/E], where:

E = estimated hours to complete the project

A = actual hours spent to complete the project

It is important to keep this KPI value as close to zero as possible, which indicates that you are bidding on projects more accurately.

Just tracking this number is a great first step towards better bidding, and you can get the necessary data to calculate it from any timesheet system, including a paper one. Automated timesheet systems, however, are generally even more effective in this area because they often have reports to calculate the KPI figure for you.

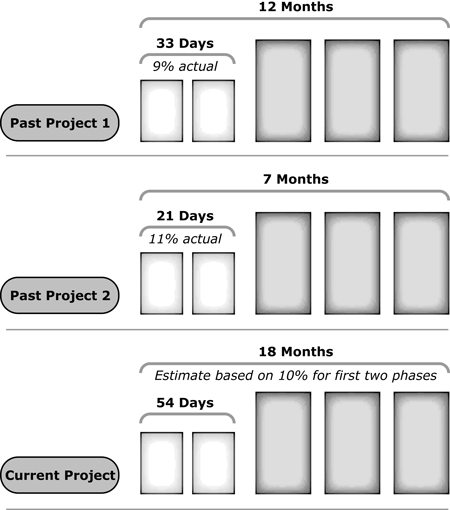

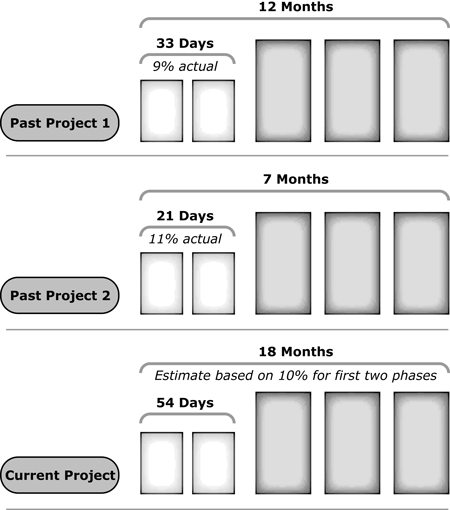

Improving adherence to your estimate can be difficult for some companies until they understand the ratio concept described above. An example of this is illustrated in the following diagram, which shows how the formula can work for any business. Your company’s magic number may not be 6-8% like Grady’s, but once you determine your own ratio for specification to total project length, you can use it again and again.

Making it Work

I currently run a software company, Journyx, and I can assure you that this project estimation technique continues to be successfully employed by many of our customers to their great advantage. It is easy to implement and you can do it too. Once you do, you will start producing laser sharp estimates before you know it. And that’s a result we can all feel good about requiring.

Happy estimating!

Don’t forget to leave your comments below

Curt Finch is the CEO of Journyx. Journyx offers customers two solutions to reach the highest levels of profitability: Journyx Timesheet – a timesheet and expense management solution for the entire enterprise – and Journyx ProjectXecute – a solution that unites project and process planning with resource management. Journyx has thousands of customers worldwide and is the first and only company to establish Per Person/Per Project Profitability (P5), a proprietary process that enables customers to gather and analyze information to discover profit opportunities. Curt is an avid speaker and author, and recently published “All Your Money Won’t Another Minute Buy: Valuing Time as a Business Resource.” Curt authors a project management blog and you can follow him on Twitter.