Best of PMTimes: Closing a Project: What, When and How

Projects, by nature, are to be closed. I am sure you know this. The two authorities made this obvious in their definitions of what project is.

Take a moment to review the definitions from PMI and AXELOS.

A project is a TEMPORARY endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service or result. (PMBoK Guide 6th Edition)

The above is the definition of a project by PMI (Project Management Institute), an organization founded in 1969, with headquarters in the USA and who has been providing guides, standards, and certifications, amongst other things, on project management since its inception. The key word is that definition is TEMPORARY, which literally means must have a start and end time.

Let’s move over a minute and take a look at the definition of a project from another body.

A project is a temporary organization that is created for the purpose of delivering one or more business products according to an agreed business case (Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2, AXELOS)

One thing is common to the two definitions. Did you see it? Yes. It’s the word TEMPORARY. A project is temporary and must be closed. Don’t confuse the term TEMPORARY with SHORT. I have got few of this concern from some of the students I train. A project can be for between 1 month and 36 months. It just means it must start and end at a particular date

Now, let me take you through the WHAT, WHEN AND HOW of closing a Project.

Note: I will not discuss whether the project is successful or failed.

WHAT is Closing A Project?

It’s has been established that every project has a start date and an end date. So, the process of completing the work on the project to an end is exactly what closing a project is. Nothing more, nothing less. If you are not closing an exercise or ending an exercise, then you need to know that the exercise isn’t a project.

It could be an operation. One of the differences between a project and an operation is that while projects are temporary, operations are ongoing and continuous. No matter how long the duration of a project is, it must end.

WHEN do you CLOSE a Project

Well, there are three circumstances under which a project can be closed. Yeah, THREE! One out of every ten readers of this article will find this surprising. Just give me a second and I will explain the three times.

1. When the project has delivered all the objectives and/or RESULT.

This is probably the most popular and most desirous time when a project should be closed. At the beginning of the project, a set of objectives, deliverables, and results were set. The PM and the whole organization rolled up their sleeves and started working towards building and delivering the objectives and deliverables for the project. Once the objective is met and the deliverables completed and accepted by the Project Sponsor/owner, it is time to close the project. Reason? The PM and the team have completed all they committed to, and there isn’t anything left to do on the project. What if there is a modification or an addition to the deliverables of the project. Well, that’s called scope creep, if there is no adjustment to other components that may be affected, and once the addition didn’t go through change control for approval, and no re-baseline, then it has to be initiated as a new project, after closing the current project.

For PRINCE2, Once the project has delivered what was specified in the business case of the project mandate, while for PMI, once it has developed the content of the approved scope.

2. When the objectives of the project can’t be met again

This is often called TERMINATION. Hopefully, it can be done early.

This is usually not a very pleasant one, but it’s usually a reality. It could be as a result of the complexity of the project or a combination of many other things. I recall working on a project with some client in the financial services industry a few years back. The business case and feasibility were highly optimistic and the organization decided to invest in the project hoping for the objective to be realized. However, after series of attempts, efforts, and re-baselining by the project team and the stakeholder, it became clear to even the blind stranger that the approach and the technology chosen for the project couldn’t meet the objective, the organization had to terminate the project for that same reason.

At times it could be that the organization had spent so much money on the project, yet they haven’t realized any benefit and at every point in time, there was no sign that the project would still deliver the objective.

Please note that in most cases, the project manager and the team are not responsible for this, and often should not be blamed.

Advertisement

[widget id=”custom_html-68″]

3. When the objective of the project is no longer needed

This is often called early termination.

We live in a dynamic and constantly changing environment, and there are many actors and factors driving the market and corporate space. Most of these factors could be a technological change, a governmental policy, a change in strategy and direction for the organization etc. PRINCE2 advises that at every point on the project, the project organization should continually check for business justification, to ensure the business case is still valid. If at any point the organization realizes that the business case has become invalid, the only thing left is to close the project. A typical example was a project I was working on for a client to penetrate a new market and release a product that would solve a particular challenge. We were about 45% into the project when the government introduced an initiative that would address a similar challenge at no cost. It became obvious that the product would not make many sales, hence the objective and business case became invalid. We had to terminate the project immediately. This is better than going head to complete the project. Organizations don’t just initiate or complete a project for the mere sake of completing a project, the product of the project must be valid all through and the end product must be desired and desirable at all time.

Another example was a consulting project I was working on with a startup to rebrand the company. Midway into the project, there was a merger and acquisition with another company it became instantly known that there was no need to rebrand the company anymore. Again, this could be at no fault of the project team.

In the next section, I would highlight how to close a project, irrespective of when it is closed.

HOW to close a Project

No matter when. You need to close the project. About three years ago, I worked on a research project with about twelve other professionals to review project management processes and health check of organizations within three continents, and we found out that a lot of organizations don’t close projects well, and this is quite worrisome. As they were completing one project, the team was being drafted to other projects or assignment without proper closure process. Hence the reason I decided to write this article.

This process will be broken that into two different sections. The first section will highlight steps to closing a project whose objectives have been met, while the second would highlight the steps to close a project whose objective is either not needed again, or can’t be met.

How to close a project whose objective has been met.

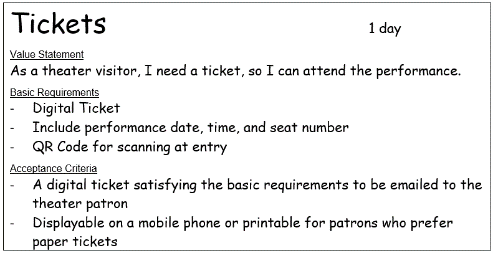

- Confirm that all the deliverables have been completed and accepted by the appropriate approving authority. Here you will need to reference your plan, specifically your approved scope and acceptance criteria

- Obtain formal acceptance and approval (this could be by way of formal SIGN-OFF or whatever method has been agreed upon).

- Close any procurement component of the project.

- Gather the team and update lessons learned on the project.

- Release all resources and provide feedback as required.

- Complete end of project report and archive project information.

- Celebrate. And I mean it.

How to close a project whose objective can’t be met or whose objective is not needed again

- Validate the reason for the early termination.

- Determine all the deliverables that have been created so far, and ensure they are accepted.

- Obtain formal closure notification from the Sponsor.

- Close any procurement engagement.

- Update lessons learned with the team.

- Release resources and complete end of project report, capturing the stage the project was at when it was closed, the reason it was closed and the lessons learned and archive project information.

- Celebrate (if you have the courage to).